‘Tradition Reborn’ – introducing innovative and pioneering new image of Japan in Europe

We were invited by the DRINK JAPAN team to join other trade professionals for Sake and Whiskey Tasting event in London so we could experience first hand the drinks, brands and producers redefining the Japanese drinks industry.

Sake, Japan’s traditional rice wine, is a drink steeped in centuries of craftsmanship, culture, and religious significance. It has played an essential role in Japanese society, from ceremonial offerings to communal celebrations. However, despite its deep historical and cultural roots, sake has been experiencing a noticeable decline in popularity in Japan.

The history of sake, or nihonshu, is believed to date back over 2,000 years, closely linked to Japan’s rice cultivation. While rice was introduced to Japan from China, the unique brewing method that creates sake is distinctly Japanese. Sake’s earliest forms were basic, evolving from a rudimentary fermentation process in which people chewed rice to mix it with enzymes in their saliva. This traditional method, called kuchikami no sake (mouth-chewed sake), was used in communal and religious settings.

By the 8th century, during Japan’s Nara period, sake production began to be organised, particularly in temples and shrines where it was used as offerings to Shinto gods and enjoyed during festivals and sacred rituals. This link between sake and the spiritual world helped elevate the drink’s status in Japanese culture. The imperial court also began to refine and codify sake-making techniques, solidifying its presence among Japan’s elite.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), sake brewing expanded across the country, especially in regions with favourable climates for rice cultivation. New brewing techniques were developed, and regional variations of sake began to emerge. Sake evolved from a ceremonial drink to one enjoyed in everyday life, with different types, such as junmai, daiginjo, and honjozo, each offering a unique profile depending on how the rice was polished, fermented, and handled.

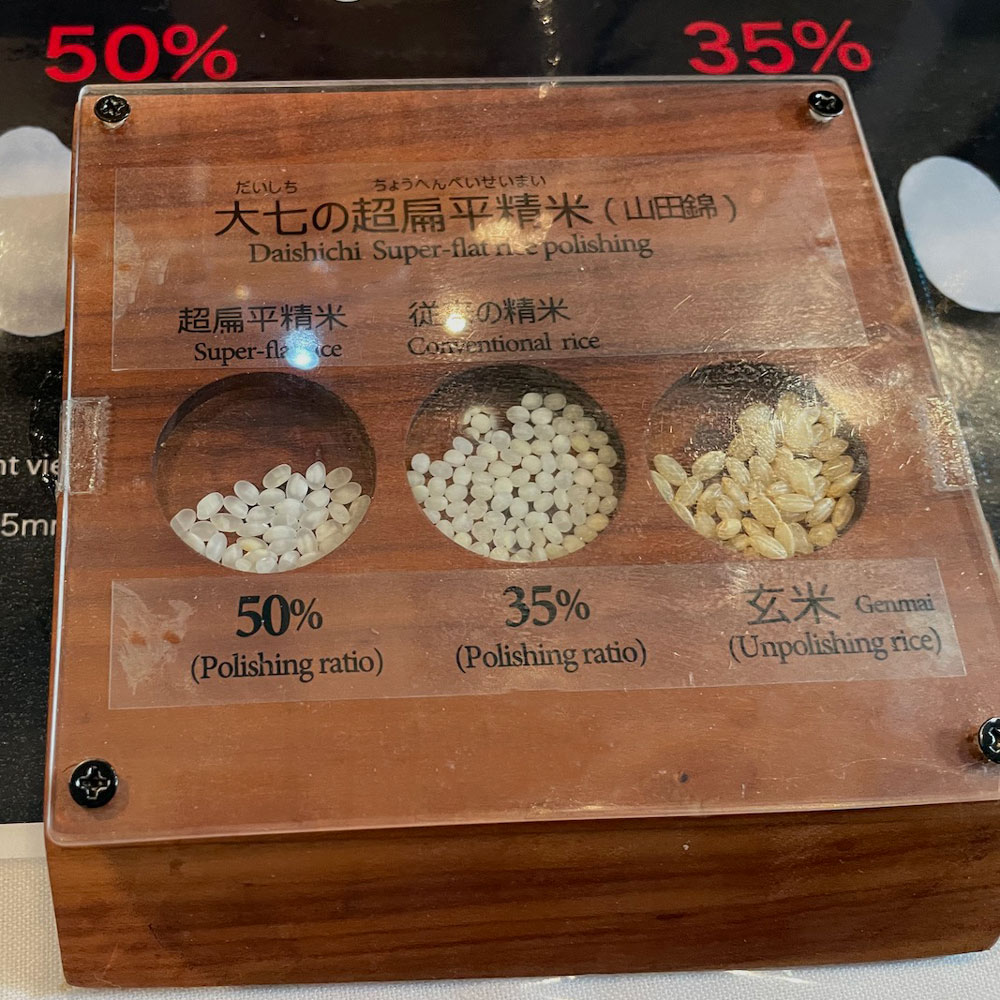

The process of making sake is a combination of tradition and skill, requiring meticulous care at each stage. The four main ingredients—rice, water, koji mold, and yeast—undergo a multi-step fermentation process. It all begins with rice, which is polished to remove the outer bran and expose the starch core. The more the rice is polished, the lighter and more refined the sake will be, as in the case of premium daiginjo sakes.

The next step is steaming the rice and adding koji, a mold that converts the rice starch into sugar. This is a crucial stage that determines the flavour profile of the sake. Water, which is plentiful in Japan and varies greatly by region, is another critical factor in the brewing process, as it influences the minearility and taste of the final product. The fermentation process is more complex than typical alcoholic beverages, involving multiple parallel fermentations that simultaneously convert starch to sugar and sugar to alcohol. The result is a drink that ranges from sweet and fruity to dry and earthy.

Sake brewing is a seasonal craft, traditionally taking place during the colder months. Each stage, from fermentation to pressing and filtering, requires close attention to detail. Breweries, known as kura, are often led by a toji—the master brewer—who commands years of experience and traditional knowledge passed down through generations. The expertise and precision needed to create quality sake reflect the deep cultural significance the drink holds in Japan.

For much of Japan’s history, sake was not just a beverage but a symbol of community, spirituality, and celebration. It was integral to religious ceremonies, such as weddings and New Year’s celebrations, where families and communities would come together to share omiki, sake offerings for the gods. Sake has also been part of kagami biraki, a ceremonial opening of sake barrels during special events, symbolising harmony and good fortune.

The act of drinking sake also carries social and cultural etiquette. It is customary to pour sake for others and not for oneself, reflecting Japan’s emphasis on respect and togetherness. Serving sake, whether warm or chilled, is seen as an act of hospitality, and its flavors are often carefully paired with Japanese cuisine, enhancing the dining experience.

Despite its historical significance and deep-rooted tradition, sake consumption in Japan has been steadily declining for several decades. In the 1970s, sake accounted for about 30% of Japan’s alcohol market. Today, it hovers around 7%, as changing tastes and lifestyles of the modern Japanese consumers, especially younger generations, have gravitated toward beer, wine, and cocktails. These beverages are seen as more fashionable and accessible, especially in urban areas where international cuisine and culture are prevalent. Beer and wine, in particular, are often viewed as more versatile for casual drinking and social settings, while sake is perceived by some as a drink for special occasions or older generations.

For many young Japanese, sake is often associated with formality and tradition. The intricate brewing process and classification system (with terms like junmai, ginjo, and honjozo) can be intimidating for casual drinkers. Unlike beer or cocktails, sake is less likely to be viewed as an everyday drink, and its traditional image may alienate those who are looking for modern, easy-to-understand beverages.

Japan’s aging population and declining birthrate have also played a role in the decreasing demand for sake. As older consumers, who traditionally drank sake, pass on, there are fewer young people to take their place in sustaining this market. In rural areas, where many sake breweries are located, depopulation has further reduced local demand.

Globalisation and market competition enabled the increasing availability of imported alcoholic beverages, such as wine from Europe and craft beer from the U.S., has given Japanese consumers a wider range of options. Global trends have made these drinks more appealing to a cosmopolitan audience, pushing sake to the periphery in Japan’s domestic market. While sake has gained popularity internationally, with exports growing, this has not compensated for the decline in domestic consumption.

Despite these challenges, sake is far from disappearing. In fact, there has been a recent push to revive and reimagine sake for modern audiences. New breweries are experimenting with innovative brewing techniques, and younger toji are introducing sake that pairs well with global cuisines. Additionally, the growth of sake exports, particularly to the U.S. and Europe, where appreciation for Japanese culture and cuisine is rising, suggests that sake’s future may lie in its ability to adapt and evolve while preserving its rich heritage.

Ultimately, sake remains a deeply significant part of Japan’s history and culture. As the industry navigates the challenges of market trends, it will continue to find new ways to celebrate and honour this centuries-old tradition.

Whiskey has become incredibly popular in Japan due to a combination of historical factors, cultural appreciation, and a deep commitment to craftsmanship. Whiskey was introduced to Japan in the late 19th century during the Meiji Restoration, a period when Japan was rapidly modernising and adopting Western customs. However, it wasn’t until the early 20th century that Japanese whiskey production truly began. Masataka Taketsuru, considered the father of Japanese whiskey, traveled to Scotland in 1918 to learn the art of whiskey-making. Once back in Japan, he applied the Scottish techniques he had learned, which eventually led to the establishment of major Japanese whiskey distilleries, such as Suntory and Nikka.

One of the reasons whiskey flourished in Japan is the country’s cultural emphasis on craftsmanship, known as monozukuri—the art of making things with a meticulous attention to detail. Japanese distilleries applied this ethos to whiskey-making, focusing on perfecting the balance of flavors and textures, much like they did with sake or tea.

This dedication to quality has resulted in Japanese whiskeys earning international acclaim. Brands such as Yamazaki, Hibiki, and Hakushu have won numerous awards, with Yamazaki’s Single Malt Sherry Cask being named the best whiskey in the world in 2015 by Whisky Magazine. The care taken in blending, aging, and selecting ingredients has helped Japanese whiskey earn a reputation for refinement and elegance.

Whiskey fits seamlessly into Japanese social and drinking culture. Whether at a business dinner, a bar with friends, or a quiet evening at home, whiskey is viewed as an ideal drink for various occasions. Japan’s izakayas (pub-style restaurants) often serve whiskey, especially in highball form, making it a common choice for social gatherings. Whiskey also resonates with the notion of omotenashi, the Japanese concept of hospitality. Offering a high-quality whiskey, carefully poured and enjoyed slowly, can be seen as an act of respect and care for one’s guests, which further elevates its cultural standing.

Japan has developed its own unique whiskey-drinking culture, different from those in Scotland or the U.S. Besides the highball, whiskey is often enjoyed neat or on the rocks. In some cases, it’s served with a single large ice cube—an art form in itself, where bartenders skillfully carve ice into perfect spheres to slowly melt without diluting the whiskey too quickly.

Whiskey’s popularity in Japan is the result of a perfect blend of historical introduction, cultural adaptation, and a deep commitment to craftsmanship. By refining whiskey production methods and tailoring them to local preferences, Japan has created a whiskey culture that stands alongside its Scottish and American counterparts. The combination of high-quality production, global recognition, and integration into Japan’s social life has made whiskey more than just a drink—it’s a symbol of refinement, tradition, and modern sophistication in the country.